This year had a lot of personal milestones. We bought our first house. We got married (for real this time, with lots of real people in attendance). I got a new job. And, as ever, I didn’t read nearly as many books as I’d have liked to. But I did read some gems this year which really changed the way I think and had a profound impact on me.

If I could only recommend one book it would be:

Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire’s Slaves by Adam Hochschild

I’m a huge fan of Hochschild. King Leopold’s ghost is one of the most horrificly brilliant accounts of the brutality of colonialism. In this history of British abolitionism Hochshild notes that ending slavery would have seemed as unlikely in eighteenth-century England as banning automobiles does today, and that even those on the vanguard of abolitionism found advocating for freeing current slaves to be a step too far.

He also shows that Caribbean slavery was, by every measure, far more deadly than slavery in the American South. This was not because Southern masters were the kind and gentle ones of Gone with the Wind, but because cultivating sugar cane by hand was—and still is—one of the hardest ways of life on earth. Because of the extraordinarily low birth rate and the early deaths from disease, Caribbean masters depended, far more so than planters in the American South, on a constant flow of new slaves.

As cultural reference points of slavery increasingly focus on the American South, it is easy to forget how deadly the Caribbean was for slaves, and how this was caused primarily by the British.

His deft examination of the anti-slavery movement is no hagiography, although the more you read about Thomas Clarkson, a committed Quaker activist who who pioneered the use of petitions, eyewitness accounts, and even an early, innocent form of direct-mail solicitation, the more you think he should be a household name and the more every campaigner should learn his story.

In particular there are analogues to climate activism. At the heart of the capaign to abolish slavery there was a tension between the revolutionaries and those more conservative in nature. Although radical in confronting a practice so interwoven with the economy of the empire and accepted throughout the world, the movement generally argued against slavery not in the name of a new social order, but rather as a continuation of Christianity and British law. Similarly today you see the tension between Green advocates who want to upend the world order and those who see green technology as a continuation of the progress made under capitalism

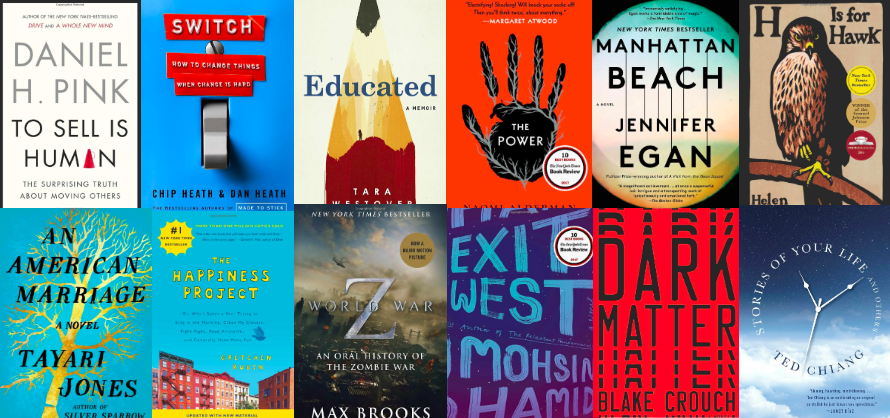

Other highlights include:

American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis by Adam Hochschild

Did I mention I was a Hochschild fanboy? In this book he examines the four years of American history from 1917 to 1921. The United States during that time saw a swell of patriotic frenzy and political repression rarely rivaled in its history. President Woodrow Wilson’s terror campaign against American radicals, dissidents, immigrants and workers makes the McCarthyism of the 1950s look almost subtle by comparison. As we go into a potentially defining election year, and possibly disastrous outcome, it is humbling to read that US democracy has survived some very dark days.

Gambling on Development by Stefan Dercon

Oh how I wished I’d had this book ten years ago. The opening chapters beat any number of longer winded attempts at summarizing a swathe of development economics. He’s a punchy writer, and as former chief economist at the UK Department for International Development (DFID), a professor at Oxford and, until recently, a policy adviser to the UK Foreign Secretary, you can tell he’s had a lot of practice at explaining complex topics to dummies.

His big idea rest on the importance of elites and how they are required to mkae a bet on development if the wider economy is to flourish.

‘A development bargain is a specific form of elite bargain, one of many possible ones. It is an agreement among those with power that growth and development should be pursued, even if they disagree over policy details. Countries with a development bargain tend to have three features in common: 1) the politics of the bargain are real and credible, not just some vague official statement or announcement; (2) the capabilities of the state are used to achieve the goals of the bargain, but, importantly, the state avoids doing more than it can handle; and (3) the state possesses a political and technical ability to learn from mistakes and correct course.’

Basically, countries get the leaders their elites deserve.

His argument is convincing, although he slightly struggles when it comes to explaining the composition of elites and how to better cultivate an elite group that is willing to a make a big bet on development. I found myself constantly thinking about the debate between access and quality in education, and how this impacts how elites would think about development. If you ascribe to a view that elites really are crucial, it becomes even more important to ensure that there is an education system that is getting elites highly literate and numerate. Obviously the counter to that is that you need wider access to to education so that the elites can be drawn from a wider strata of society, but that seems naively optimistic on how egalitarian most societies are.

Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming by Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway

The history of corporate-financed public relations efforts to sow confusion and skepticism about scientific research is long, infuriating, but ultimately uplifting, as the vast majority of the time they fail. What you see is that most people do trust science on most things, and most people trust experts on most things. But the infuriating thing is that it only takes a few wrenches in the machine to really slow things down.

Most of the time we reject scientific findings because we don’t like their implications. It will make us do something inconvenient (i.e stop smoking with our friends, travel less, eat less delicious food). It’s why scientists have to be in the business of selling the better world that comes from their findings.

Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon by Michael Lewis

This dude is always in the right place at the right time. He’s come in for some stick for not jamming in the knife deeper to SBF, but whatever this is a captivating adventure and as always his prose is just…mwa.

Billion Dollar Whale: The Man Who Fooled Wall Street, Hollywood, and the World by Tom Wright & Bradley Hope

Jho Low is the villain late stage capitalism needs. This is the story of how he got through nearly $5 billion dollars in the 1MDB scandal. Ok so this book does have a heavy dose of wealth porn and it you can’t help be captivated by the excess (Britney jumping out of his birthday cake in a gold bikini!). The intriue comes from how many credible people wanted to believe -from Swiss bankers to movie producers. It seems the only person who could tell straight out it was a fraud was Jordan Belfort (the actual wolf of Wall Street) who tried to warn Leo DiCaprio about them.

Secrets of Sand Hill Road: Venture Capital and How to Get It by Skott Kupor

I just spent a year working in VC and this is the perfect primer for that world. I wish there was an equivalent handbook for the world of philanthropy.

Rogues: True Stories of Grifters, Killers, Rebels and Crooks by Patrick Radden Keefe

One of the best staff writers at The New Yorker has some of his best pieces collected in this book. He paints characters better than anybody.

I love this anecdote from Arthur Koestler - he once pointed out that when thieves were hanged in the village square, other thieves flocked to the execution to pick the pockets of the spectators. A note of warning to anybody who thinks that extreme punishment is an effective deterrent.

Becoming Trader Joe: How I Did Business My Way and Still Beat the Big Guys by Joe Coulombe

Trader Joe’s is unlike any other American grocery store. In a very good way. In this you see how pig headed it required Joe Coulombe to be to not be shifted away from his mission to create a grocery store that treats it’s customers and employers right. And gives them both access to a better way of delivering fresh food to people.

Losing the Signal: The Untold Story Behind the Extraordinary Rise and Spectacular Fall of BlackBerry by Jacquie McNish and Sean Silcoff

Better than the recent movie. It’s so easy to forget how revolutionary the little keyboard was. Hope everyone at google and apple reads this. A perfect demonstration on why you should rarely design an organization around a product.

Artemis: A Novel by Andy Weir

Two reasons to love this book. One, Kenya has become the preeminent nation in space exploration due to a savvy government and it’s shoter distance to the moon due to being close to the equator. And two, the epiogue chich napkin maths out the economics reuquired to make viable tourism industry and community on the moon is just brilliant.

Birnam Wood: A Novel by Eleanor Catton

I read The Illuminaries ten years ago and it stuck with me. Catton has such a knack with plot. Birnam Wood is just as good. You start to think it’s going to turn into a bit of treatise on how hard it is to stay true to your morals as a revolutionary but it turns into storming corporate thriller. I dare you to read it in under 2 days.

Same as Ever: A Guide to What Never Changes by Morgan Housel

The best blog writer out there condenses so much wisdom into this little book. Read it in two hours and then read it again.

History never repeats itself; man always does. —Voltaire

The wise in all ages have always said the same thing, and the fools, who at all times form the immense majority, have in their way, too, acted alike, and done just the opposite. —Arthur Schopenhauer

The Bill Gates Problem: Reckoning with the Myth of the Good Billionaire by Tim Schwab

I wish this was better written. The lazy rhetorical questions and speculation overshadow some really important journalism. it’s hard to read the section on the links to Epstein and not come out of it feeling very worried.

Soccer Books!

I’m obsessed with football. I’d call it an addiction as I’ve tried to stop. But I can’t and I’m stuck with it. At elast it’s not baseball or some other sport that onyl one country cares about. At least it truly is an international game. I’m stuck with it so I figured this year I would buff up a bit and actually study it.

The Club: How the English Premier League Became the Wildest, Richest, Most Disruptive Force in Sports by Joshua Robinson and Jonathan Clegg

There are so many wheeler dealer characters at the birth of the Premier League. It’s a tale of how free markets can create a better product that brings value to so many more people.

Inverting The Pyramid: The History of Soccer Tactics by Jonathan Wilson

Jonathan Wilson is by far and away the best writer on football tactics out there. His weekly column in the Guardian is unmatched. This minutely researched history, along with formations, of all the great sides of the past 150 years is masterclass. It also shows a Hegelian view of how new tactics emerge. Pep’s inversion of fullbacks can look like a complete revolution but when you see tactics from some of the teams of the 30s and 40s you see them do soemthing very similar. An important trick in everything: to develop foresight, you need to practice hindsight.

The Mixer: The Story of Premier League Tactics, from Route One to False Nine by Michael Cox

More focused on the recent game and a good reminder that the Premier League has often not been great at learning from what is happening in the rest of the world.

My Autobiography: The autobiography of the legendary Manchester United manager by Alex Ferguson

The greatest. He did it simply and in this book you can see his obsession but also his clarity. Never one to mince words this contains a lot of wisdom in a short book.

And finally…

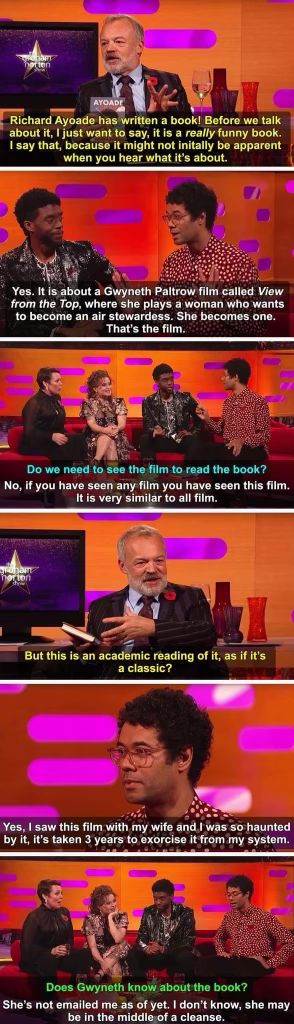

Ayoade on Top by Richard Ayoade

It takes remarkable skill to write a book based on the Gwyneth Paltrow 2003 movie View from the Top. Paltrow herself called it “the worst movie ever”.